FEATURE

Over 50 Years Later, Vinton’s “Melody of Love” Still Connects

by David Jackson

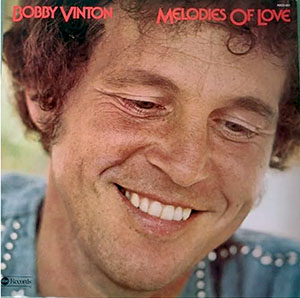

There has never been a time in my life when I wasn’t familiar with the song “My Melody of Love” by Bobby Vinton. The song came out when I was just five years old. I know it is risky to trust childhood memories, but as best I can recall, I first saw the cover of the album “Melodies of Love,” where the song appears, at my Polish American grandparents’ house. I can’t remember when or where I first heard the song, mostly because it has always just been there: on the radio, TV, turntable, or performed live by a polka band. I know I am not alone in loving this song and knowing it was and still is a big deal for the Polish American community.

More than 50 years ago, in November of 1974, “My Melody of Love” reached number three on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The song included these unforgettable Polish language lyrics in the chorus:

Moja droga, ja cię kocham,

Means that I love you so.

Moja droga, ja cię kocham,

More than you’ll ever know.

Kocham ciebie całym sercem,

Love you with all my heart ...

While the English lyrics that follow the Polish lyrics are not always a literal translation, the fact that a song with Polish lyrics performed so well in the charts sent shockwaves throughout the Polish American community. It is believed to be the first time that a song with Polish lyrics had ever charted this well in the United States, and it may be the only time this has happened.

Vinton was nearing forty years old when the song came out, and he reports that he wrote it because his mother said he should sing something for the Polish people, because in return they would love him forever. More specifically, according to an interview by Rob von Bernewitz, Vinton says he was proud of how he could sing in Italian, Spanish, and German, and his mother said, “Hey, you sing in Italian pretty good. You should be singing in Polish.” Vinton replied, “Mom, there are no Polish songs that rock and roll stations are going to play,” and she answered, “How do you know? Nobody ever did it. Why don’t you write a song that says ‘moja droga,’ which means my loved one.” Vinton relented and recorded the song, then discovered, “It was not only a hit record, but a happening for Polish people.”

Vinton has a chapter in his official autobiography where he writes the story of how, in his view, the song would be just another tale of a recording striking the fancy a large segment of the music buying public if not for two things, one of which was how the song, “had an unspoken message of social importance.” He explains what he thinks that message is by interpreting the English lyrics. What or who is the lost love about which he is singing?

I’m lookin’ for a place to go so I can be all alone

From thoughts and memories

So that when the music plays I don’t go back to the days

When love was you and me ...

Wish I had a place to hide all my sorrow, all my pride

I just can’t get along

‘cause the love once so fine keeps on hurtin’ all the time

Where did I go wrong?

He explains, “My love, so wrapped up in that melody that it bursts out in the language of my childhood, Polish, is a symbol of many loves.” Further, he writes, “…the expression is so basic it can come out only in the language of (my) father and his father’s father.” He says the loss about which he was singing is the loss of his audience, the beginning of his decline into relative obscurity, and his desire to win back his fans. Then he writes, “The small point I was able to make is that to be an American means, among other things, to be different and to be proud you’re different. In the past we’ve often been asked not to be different, to submerge our cultural backgrounds. After the song became a popular success, disc jockeys would come up to me and would ‘confess,’ as they put it, that they were Polish. They had changed their names. It’s more difficult to change your age or to change the color of your skin.”

Vinton is said to have sold 75 million records during his career, and more than a million of these were “My Melody of Love.” Vinton played massive venues at the height of the song’s popularity, and starred in his own syndicated variety show between 1975 and 1978. Chicago Mayor Richard Daley even dubbed Vinton “The Polish Prince,” a nickname that has stayed with him. Daley is said to have come up with the nickname when explaining why he arrived late for a dinner with the king of Sweden because he had been at a Vinton concert. For nine years Vinton performed at his own theater in Branson, Missouri, and only retired from performing in 2015 at the age of 80 after a serious bout with Shingles.

Outside the Polish American community, the movement that surrounded Vinton’s grand second act was not always received favorably. In a New York Times review of Vinton’s late 1974 Carnegie Hall performance the headline reads, “Music: Polish Power/Bobby Vinton, at Carnegie Hall, Takes Up Current Fad in Smooth Performance.” Asserting that Vinton has, “… found a new way of increasing his audiences, mining an ethnic vein previously left untouched in his musical field,” the review points out Vinton dancing the polka on stage, adding Polish references to non-Polish songs, and crowning Miss Polish New York. The review concluded with, “It may be kielbasy, but Mr. Vinton prepares it with high grade professionalism.”

In one short article, the Times critic diminished Vinton’s Polish songs and references as a fad, suggested he was doing it for the money and just pandering to his audience, and insulted Polish cuisine. Quite an achievement for the nation’s newspaper of record.

Now more than 50 years old, the song is still remembered fondly by Polish Americans, and with good reason. During the era of Polish jokes and Poland’s subjection to communism, it gave Polish Americans a way to express pride in their Polish-ness. I think it is fair to say that it also helped inspire a small movement in the Polka genre to write songs asserting Polish pride, and that is a good thing that continues today.

I recently asked someone about the song, and they replied, “Great … Now I’ll have that song stuck in my head all day.” I thought, “you’re welcome.” And thank you Bobby Vinton!

David J. Jackson is Professor of Political Science at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. His major research interest is the interactive relationship between politics and culture. He is the author of the book Entertainment and Politics: The Influence of Pop Culture on Young Adult Political Socialization (Peter Lang Publishing, 2009), as well as scholarly articles in such journals as Political Research Quarterly, Polish American Studies, International Journal of Press/Politics, and Journal of Political Marketing. In 2007-2008 he was a Fulbright Fellow at the University of Łódź. His book Classrooms and Barrooms: An American in Poland, was published in 2009.

Bobby Vinton’s “My Melody of Love” was released on ABC Records in 1974. The song proved to be a successful comeback for Vinton and is included on his album “Melodies of Love,” also released on ABC Records.